Today I want to share an experiential futures project cocreated with a group of individuals usually pushed to the margins in every way. Here they appear in the spotlight, with a call for their dreams to be recognised and their voices heard.

Hiba, aged 9. Vision: future paediatrician. "I have always wanted to help children. I am kind and loving, and therefore an excellent doctor that children can trust."

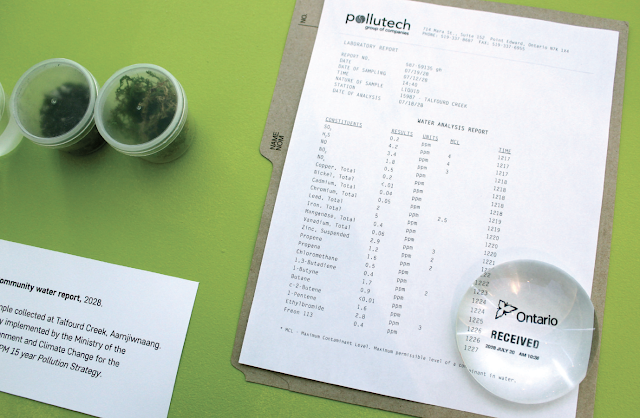

Photos and captions: Meredith Hutchison / International Rescue Committee [via IBT]

Photos and captions: Meredith Hutchison / International Rescue Committee [via IBT]

The premise of "Vision Not Victim", created by photographer Meredith Hutchison, is straightforward. The girls are asked about what they want to be when they grow up, and then they do a photo shoot where they dress up as if it has happened, and talk about how it came to be, speaking as their future selves.

Supported by the International Rescue Committee, a global humanitarian and aid organisation, this iteration of the program was carried out in Syrian refugee camps in Jordan (video), after being piloted in the Democratic Republic of Congo (video).

IRC explains:

Every girl designs and directs her own shoot where she poses as her future self — achieving a goal. Whenever possible, we try to do these shoots on location, in actual working environments, so girls can meet people in their envisioned field and truly step into their future.

As empowering as the photo shoot experience itself may be, the outcomes don't stop there: "Perhaps the most moving and impactful part of the program is the moment when the girls share their photographs. They beam as they receive their images and run to show parents and friends."

An opportunity to see and do differently ripples outward from this bold declaration of possibility.

An opportunity to see and do differently ripples outward from this bold declaration of possibility.

Haja, aged 12. Vision: future astronaut. "Ever since we studied the solar system in primary school, I have wanted to be an astronaut. I love being an astronaut because it lets me see the world from a new angle. In this society my path was not easy – many people told me a girl can’t become an astronaut. Now that I have achieved my goals, I would tell young girls with aspirations to not be afraid, to talk to their parents about what they want and why, to always be confident and know where you want to go."

Fatima, aged 16. Vision: future architect. "When I was young people told me that this is not something a woman could achieve, and they encouraged me to pursue a more 'feminine' profession. Now that I’ve reached my vision, I hope I am a model for other girls."

Fatima, aged 12. Vision: future teacher. "In this image, it is the early morning and I am waiting in my classroom for my students to arrive. I teach younger children to read and write Arabic."

Amani, aged 10. Vision: future pilot. "I love planes. I finished my studies and found a way to get to flight school. Now, not only do I get to live my dream, but I also get to help people travel, to see the world, and discover new places."

Muntaha, aged 12. Vision: future photographer. "As a professional photographer I use my images to inspire hope in others – to encourage love and understanding."

Notice how they speak from inside the future scenario, visualising and roleplaying their accomplishment; not "I want to..." but "I have..."

The import of this shift in imagination can be profound. Here's an example related by the photographer, reported by CNN:

Hutchison remembers one girl who was engaged to be married though she was younger than 13. (The photographer asked that the girl's name not be used to protect her identity.)

"I distinctly remember the moment when we showed her parents her vision images. Her mom was just ecstatic and her father ... was absolutely silent -- and smiling -- but silent, thumbing through the images.

"I think he was just in awe that this could be his daughter."

By the end of the program, the parents had called off their daughter's engagement and had committed to helping her finish her education.

That's the power of the photographs -- something unquantifiable happens to the girls, Hutchison says.

I recently read Rebecca Solnit's book Hope in the Dark. which focuses especially on citizens and activists pursuing what may appear to be lost causes. It's an extraordinary work –– I wholeheartedly recommend Solnit's writing in general –– and her analysis of how hope functions manages to be simultaneously tough-minded, filled with compassion, and uplifting.

To hope is to give yourself to the future, and that commitment to the future makes the present inhabitable. [...] Despair demands less of us, it's more predictable, and in a sad way safer. Authentic hope requires clarity––seeing the troubles in the world––and imagination, seeing what might lie beyond these situations that are perhaps not inevitable and immutable.In a similar spirit, it's elevating to find a project carried out in such desperate circumstances, contributing to the possibility of those circumstances being transformed.

Having attempted at various times to narrow that gap by bringing futures to life in unscripted environments (albeit so far in no setting as fraught with complexities as a Syrian refugee camp must be), I have great appreciation for what Meredith and her collaborators have done here.

We can readily grasp the transformative potential of a well-wrought experiential scenario –– that is, making a possible future vividly available to think and feel today –– whether at the scale of a country (as in Tunisia, during the Arab Spring, with the aspirational 16juin2014 campaign); a group (as in Hawaii 2050); or an individual (as in Derren Brown's apocalyptic wakeup call to one troubled English kid, which painstakingly simulated the end of the world exclusively for him). But examples as fully realised as these can be resource intensive.

(More than a year after first hearing about this project, I've noticed that its structure appears to describe the same arc as the generic Ethnographic Experiential Futures process recently shared here: MAP [unearthing a preferred personal future, in this case] > MEDIATE [staging the photo shoot] > MOUNT [sharing the photos with the girls and their families] > MAP [capturing reactions].)

In her award-winning final MDes project at OCAD, Foresight for Every Kid, Amy's research highlights the fact that

low-SES students are more likely to be present-oriented, chiefly a consequence of the 'tunneling' that occurs due to scarcity. Middle-class, higher-SES students, on the other hand, are more inclined to think on the future as they are less burdened by unmet needs in the present. [...] Academically successful students... are those who can imagine fairly far into the future, set goals, and defer gratification in order to work toward them. In this system, our present-oriented students' perspectives are less likely to be acknowledged, honoured, and validated. ...Foresight for Every Kid suggests that educators must first shift their mindsets, tuning in to the time perspective bias in their practices, and adjusting accordingly.In many respects of course, Syrian girls in a refugee camp in Jordan, on one hand, and low-SES public school children in Canada's largest city, on the other, are incredibly different groups and contexts.

Still, there are at least two key ways in which tracing connections across those differences might be useful.

First, to do so shows how the universally accepted right to education also entails the right to foresight. The chance to envision personally meaningful and motivational long-range outcomes is, at the individual level, a foundation on which the whole enterprise of education ultimately depends.

Since foresight is ultimately about making change in the present, enabling it is not just an "important" priority (aka worthy but perpetually deferrable), but one that needs to be recognised as urgent, too.

A corollary of this understanding that yes, there is dark to be found everywhere, is the space for hope; the opportunity, in Solnit's words, to make a "commitment to the future [that] makes the present inhabitable".

Herein lies an opportunity for meaningful engagement and contributions from diverse concerned citizens –– educators, futurists, designers, artists, and the rest of us, too –– far and near.

Rama, aged 13. Vision: future doctor. "Walking down the street as a young girl in Syria or Jordan, I encountered many people suffering – sick or injured – and I always wanted to have the power and skills to help them. Now, as a great physician in my community, I have that ability."

Merwa, aged 13. Vision: future painter. "In this image, I am a popular painter, working on a landscape in oils. I have my own gallery where I sell my paintings and sculptures. My hope is that my artwork inspires peace in the world and encourages people to be kind to one another."

Malack, aged 16. Vision: future policewoman. "I’ve always wanted to be a policewoman because the police not only keep people safe, but they also create justice in society. I also work to inspire other young girls to become policewomen – supporting them to dream about their future and thinking about how they will overcome obstacles."

> Foresight is a right

> Ethnographic Experiential Futures

> Wish you were now

> The act of imagination

> Where every day is career day

> Second nature

> Apocalypse for one

> Tunisia's national-scale Experiential Scenario